Dear all,

We are very pleased to notify you of Haruna Morohoshi’s solo exhibition at Art Lab Akiba from 27th October to 7th November.

For the past four years Morohoshi has been working with animation, but for this solo show she has created an installation in the gallery space and in three serial exhibitions. These will be curated by Emma Ota.

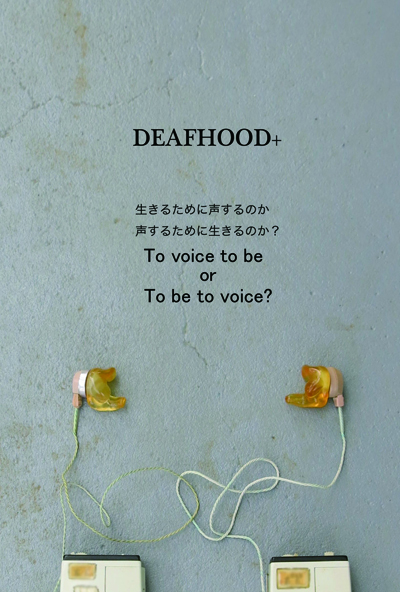

In this first exhibition she is showing an installation based on her childhood experience at school as a Deaf person. Underlying her work are ideas that address Deaf Culture, languages, the future of human beings and issues stemming from postmodernism. Some of these relate to specific pairings, such as that between deafness and hearing, while others are general and universal. Emma Ota encountered the world of Deaf Culture in order to meet with Morohoshi, and to fully understand her concepts. Ota's exhibition text deals with the intensity of the impact of this experience, together with a reflection on the importance of Deaf Culture for our future.

I hope you will come and be intrigued by the exhibition.

Kentaro Chiba

ArtistFHaruna Morohoshi

Curator FEmma Ota

ProducerFKentaro Chiba

27th October - 7th November 2015

14:00-19:00

¦This show is the first in three serial exhibitions

venue: Art Lab Akiba

Artist Statement

@

I am not sure when the consciousness of Deafhood started to reside inside me. However, I think it lay buried within for a long time.

In daily life, I don’t distinguish between the hearing and the Deaf but when I notice the situation where I am the only Deaf person surrounded by many hearing people, then I sometimes feel isolated even though we are sharing the same space. But this brings to me a positive awareness, another perspective from the different world I belong to.

This experience is not one of emotional loneliness, but a slight feeling of being upon a border.

Every past must pass away and can never dominate over me. And I greet this merely as the process of change.

Haruna Morohoshi

* “Deafhood” means “being as a Deaf person”, the term, which Dr. Paddy Ladd suggests to distinguish from “deafness”, the medical term used for hearing impairment.

Expanding Languages

“Language in Danger” was a significant book for me in my teenage years, along with Derrida’s “Of Grammatology”. One might be said to be a certain reflection of post-colonialist thought, the other the grounding of postmodernism. Andrew Dalby sets out a disturbing course of the 21st century in which over half of the world’s current languages are likely to be lost. He warns stringently against “language standardization”, and the continued colonialism enacted by the English language. As the world’s languages become more and more condensed as a result of globalization and hegemonic forces, some might feel it makes life a whole lot easier if we speak the same language (think of all the translation work I would be saved of!), and a greater understanding might pervade the Earth. (The tower of Babel has always been a keen reference here, in which human kind once supposedly shared a universal language, making their ambition unstoppable as they built a tower to rise to the heavens, only to be punished by being split into innumerable languages and scattered across the globe, leading to division and conflict). We would all like to think if we spoke the same language we would all get along much better, but Dalby demonstrates that this is not the promise that awaits us but rather the precise opposite. In fact it is the very difference which Derrida coined in “Of Grammatology” which appears to be fundamental to our tolerance. Without this language becomes hard, along with our expectations, with any deviation becoming a severe disruption. The more we speak the same language, the more we are at war, Dalby claims.

Every single language contains a macrocosm of thought, ideas, identities, culture and ways of seeing the world. With every loss of a language the possibilities of the world become smaller, the creativity and innovation of humanity becomes diminished and we suffer a cultural extinction. For every language lost, we also lose a part of ourselves.

Much has been documented upon the phenomenon of linguistic imperialism the attempted eradication of minority languages by colonialists, from the implementation of Latin throughout the Roman Empire, to Britain’s sign posting of Ireland, the genocide of Charruas in Uruguay and compulsory Japanese education in the Asia Co-prosperity Sphere. But the area of sign language has been an area often overlooked in this discourse until recently.

In 1880 “The 2nd International Congress on Education of the Deaf"”, held in Milan, a decision was taken which would change the course of Deaf education for the next 100 years, it was decided to prioritize Oralism (verbalization and lip reading) and effectively ban the promotion of sign language in schools for the hearing impaired. In his “Understanding Deaf Culture” Paddy Ladd refers to this event as a “cultural holocaust”, an uncompromising term, but one that reflects the scale of effective cultural cleansing which occurred through this policy.

This was also Haruna Morohoshi’s experience in her very early years of education, in which instead of being taught sign language, she lost time to enacting the standards of Oralism. This exhibition is not intended as an overt criticism but rather to indicate a chapter in Deaf history and Morohoshi’s personal history. Thankfully education policies began to change from the late 80s, shifting back to the essential role of sign language, but it was not until 2010 in fact that the International Congresson the Education of the Deaf (ICED) made a formal rejection of the resolutions passedat its 2nd Congress.

Despite these setbacks Deaf culture has of course flourished, but with vastly different levels of recognition around the world. If we take national sign languages as an example, there is a wide spectrum seen here, from no formal recognition of sign language to the establishment of sign language as one of the official national languages in New Zealand and Northern Ireland. Many are familiar with Gay Pride, Black Pride, the pride in holding so called “minority identities”, but we also have Deaf Pride, which clearly rejects the condition of “Deafhood” as a disability and celebrates its vibrant and diverse culture. What is particularly interesting about this culture is that it is not something passed down between parent and child (only 5% of Deaf people have Deaf parents), it is a language, identity and discourse primarily learnt through Deaf schools and as such is free from the associations of race, ethnicity and nation to a larger extent, making Deafhood a global identity, often with a much higher awareness as a global citizen.

In the introduction of his book “Understanding Deaf Culture”, Paddy Ladd uses the metaphor of a Museum to examine the warped representation of Deaf history by hearing medical experts and educators, with the true legacy of Deaf culture being consigned to a hidden back room. This appears as a reference in Morohoshi’s own approach to this exhibition, in which she attempts to reconstruct a certain phase in education and understanding of what was termed “deafness” but should have been recognized as “Deafhood”.

We are confronted by the devices of “assimilation”, to turn a linguistic and cultural minority towards integration with (or subsumption by) the majority. And we (both hearing and Deaf) are asked to question in part our own collusion with or resistance to this.

In preparation for this exhibition Morohoshi and I had many conversations, but I imposed my own language standardization, only learning a few rudimentary signs, and relying principally on written correspondence in Japanese. But as we are both non-natives to the Japanese language it was perhaps an apt compromise. In these conversations we spoke much about the gaps in language and the problem of translation, reflecting our very own condition in our communications.

In the process of discussion with the artist and being involved in the organization of this exhibition I have learnt many things, mostly about myself. In particular the following statement in Ladd’s book made a strong impression upon me. While he of course recognizes there is "not just one homogeneous Deaf culture", he also points out how political mobilization of the Deaf communit(y)/(ies), in what Spivak might term “strategic essentialism”, is in face threatened by the postmodernist rejection of a singular representation and grand narrative.

“However, I am also aware of the ironic timing of post-modernism – that is, at the very moment when the discourse of oppressed groups at last becomes visible and they are finally able to position themselves as a counter-narrative to White or Hearing supremacy, that their discourses risk being dismissed along with the Grand Narratives themselves!”

This has led me to reconsider my own leaning towards postmodern discourse, the problems of representation, the universal understanding of difference, and particularly the role of art amongst this, all of which I have been grappling with even as I write this text, but most significantly the importance of language diversity and the cultures and histories attached to this have impressed themselves anew upon me. So through this exhibition, which has now developed into a triptych to be continued over the next year or so, I hope we may see how one individual artist chooses to communicate and examine personally this culture and experience which she is attached to, and add further vocabulary to our understanding of the world.

CuratorFEmma Ota

Art Lab Akiba

www.art-lab.jp

urotankebachi@yahoo.co.jp